Absolute advantage is the ability of an individual, company, or entity to produce a good or service at an absolute lower cost than others. The cost can be lowered by producing larger quantities given the same inputs or producing a better service given the same time and effort inputs.

This can come about due to natural advantages among nations, like the availability of certain raw materials, the mineral richness of one nation over another, technological differences, educational differences, weather-related differences, or simply due to geographical location.

The theory of absolute advantage was suggested by Scottish philosopher Adam Smith in 1776 in context with international trade, suggesting specialization in advantaged goods for the sake of engaging in free trade leading to prosperity due to economies of scale.

Smith’s absolute advantage theory was considered the dominant trade theory until British economist David Ricardo suggested a comparative advantage theory in the 19th century, which takes into account an opportunity cost. (You can read the article on comparative advantage in the Pitch Labs library.) Ricardo argued that countries can benefit from trading with each other if they focus on producing the goods and services that they are best at, without foregoing the production of an alternative good or service. Given each country’s cost of raw goods and opportunity cost, if the countries focus on what they are good at, then their efficiency at the production of this goodwill improves, leading to further lowering of costs. More production, higher specialization, lower cost.

However, comparative advantage is not always easy to identify as absolute advantage.

In his book titled “On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation” (1817), Ricardo argued against Great Britain’s protectionist Corn Laws, which restricted the import of wheat from 1815 to 1846. In arguing for free trade, the political economist stated that countries were better off specializing in what they enjoy an absolute advantage in and importing the goods in which they lack an advantage.

Any advantage in the production of a good or service is collectively derived from:

- Financial cost

- Efficiency cost

Financial cost is the cost of raw materials, machinery, etc. As mentioned above, some countries may have access to cheaper raw materials for many reasons, hence their cost of production will be lower.

Efficiency cost of production refers to the speed with which a country can produce a product, even if the cost of materials is higher in that country. This could be due to educational or technological differences.

Hence, even though it may seem financially cheaper for a country to produce a certain product, it is not only the financial cost of producing that good or service that matters but also the efficiency of its production. Since efficiency eventually feeds into the final financial cost of production, we will assume efficiencies go hand in hand with financial cost, both making up what is called an absolute advantage.

Absolute advantage takes into account the sum total of the quantities produced and the cost associated with producing it.

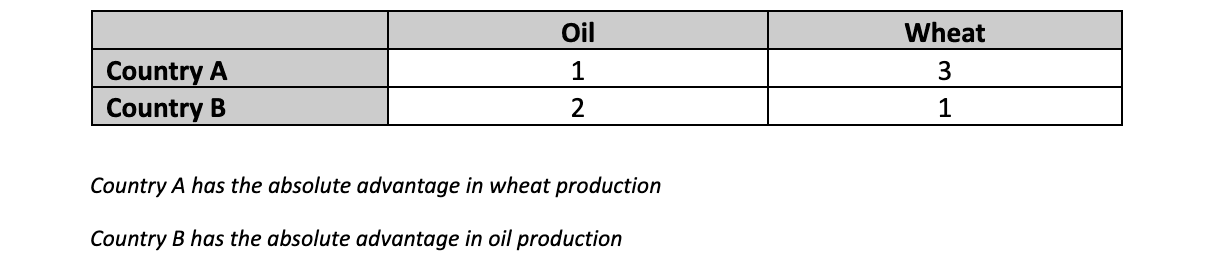

For example, let us look at two countries producing oil and wheat. Assuming all else equal—meaning the demand, raw materials, and other inputs—the following table shows the man hours needed to produce each good by the two countries.

Source: Created by Author

In the above example, if country A can produce wheat faster than country B, or at a lower cost than country B, then country A is said to have an absolute advantage over country B in wheat production.

Similarly, if country B can produce oil faster or cheaper than country A, then country B has the absolute advantage in oil production. (We will refer to Country A and Country B as Cy A and Cy B from here onward.)

In international trade markets, it may seem beneficial from an economic standpoint for Country A to produce wheat and export to Cy B. In the real world, it gets a little more complex when all the inputs and correlating products come into play. Say the absolute advantage for Cy B in oil production is minimally better than Cy A, but the difference is much wider in the production of another oil byproduct. Then it will be beneficial for Cy B to focus on the production of that byproduct for bigger profits.

In the real world, where resources are limited, businesses or societies must make a decision or market forces eventually decide for them as to what to focus on and how the resources are allocated.

Production of goods and services may get split around the globe to take advantage of the available efficiencies at each stage of production as well. Cy A may produce oil and send it to Cy B for the production of the byproducts, if it seems more profitable or if international trade treaties favor such a trade balance.

In some cases, a country may not have an absolute advantage but a comparative advantage over its competitors. Though absolute advantage theory lays the basis of trade, it does not take into account international trade policies that may allow nations with comparative advantage to trade based on their opportunity costs being lower. Practically speaking, in real life, it is equally important to factor in the foregone opportunities of what could be done with the given time and resources if one were to focus on a product versus alternative product(s) or service(s).

Whether nations focus on their absolute or comparative advantages depends on their goals, timing, or political or social agenda. Situations and raw materials availability change over time, affecting a nation’s absolute advantage, forcing it to look at what the nation continually needs to let go in order to focus on its absolute advantage. An absolute advantage does not remain constant over time and shifts due to many reasons, making it prudent to shift the strategy accordingly.